A MEXICAN JOURNEY ON VINTAGE BIKES

Words by Quentin Franco | Photography by Matt Cherubino

In collaboration with Deus Ex Machina

It was sometime between my last high-speed front-flip and seeing the carcass of a mangled motorcycle in my garage that I began to wonder if riding a 400-pound Triumph across the Mexican desert might not be the best idea. After all, my latest racing “stunt” had cost me a perfectly good helmet and a concussion that wiped the month of April off the calendar.

At that point, some would have said enough was enough with the old bike, but I still couldn’t shake the idea that there was more to be attempted on my 1972 Triumph Tr6C. These were the glorified machines Bud Ekins and Steve McQueen raced. In their day, whether it was dirt track or desert scrambles, these were the bikes to beat. Surely, the old girl deserved another try, right? I mean it wasn’t the bike’s decision to hit a bush at 50 mph, was it? So, as someone who likes learning a lesson the hard way, I bent my bike back into submission, dumped a few more quarts of oil in it, and got the call from Forrest Minchinton.

It did not take long to talk me into it. In fact, all he really needed to say was “Mexico,” and I was in. You see, for us California boys, south of the border has always been the promised land. The roads flowed with ice-cold Tecate, handed out by the most beautiful women, and every point down the coast seemed to hide its own treasure trove of waves. That, and you could eat yourself sick with tacos and ride your motorcycle in any direction you pointed the handlebars. At least that’s the romantic version of Mexico. The reality, however, is that the promise of ultimate freedom and lawlessness usually sucks in the most gullible of gringos and bites them in the ass. Lucky for me, I would be riding south with two other experienced two-wheeled cowboys.

By this point in life, Minchinton has probably logged more hair-raising seat time on a motorcycle than most of us could ever dream of. A native Spanish speaker, he cut his teeth riding waves and bikes all across Latin America, making him the de facto leader of this harebrained trip. Then there was Reid Harper, a lifelong buddy of mine. A second-generation stuntman in Hollywood, the guy is so smooth in just about everything he does you could get yourself in way over your head just trying to keep up. As far as my own experience goes, my successes were usually measured in how much abuse I could take. But like I said before, I seem to enjoy doing things the hard way. And that’s exactly what this trip was: Mexico – the hardest way possible.

It wouldn’t be the terrain that got us; we all knew that well enough. Nor would it be the threat of sitting in some Ensenada holding cell for running stop signs – those are rookie mistakes. For the three of us, this trip was going to be a test of who had the best-running, least-rattling and oil-leaking, easiest-on-the-spine, fifty-plus-year-old British bike. In that department, Harper usually won. Having put his bike in the garage after winning the vintage class at a recent desert race – the same one where I front-flipped – I was pretty sure he would show up with polished chrome and a perfectly running machine. Per usual, my bike was more of a disaster. The lovable but devious oil-in-frame model had been in pieces and mysteriously losing power since our last dance together. But I was semi-confident she’d run for at least most of the trip. I hoped. Then there was Minchinton’s bike, which was literally in pieces as we rolled up to his garage. With his typical laid-back approach, he threw on the few remaining parts, and off we went. Three experienced motorcycle riders, with way more common sense than to attempt to ride vintage Triumphs through a land that swallows modern factory-built race bikes.

The usual border crossing was a breeze, and as we hit the toll road down the Pacific this trip had all the telltale signs that it was going to be one for the books. A few tacos and a mandatory surf check later, we opened the doors and unloaded the old girls. On the outskirts of beautiful Baja wine country, we topped off the fuel and kicked the tires for an air pressure check. We slid on our open-face helmets (our teeth be damned) and threw our legs over the ancient steeds. Throwing a few shakas at the locals and dodging the street dogs that would inevitably try to gnaw our boots off the minute we rode away, we settled in for the first leg of the trip.

We hit the dirt with one goal, to reach the Pacific Ocean. Riding three-wide, we slid the old Triumphs around every slick corner we could find. Through winding mountain roads, past cattle ranches and lush overgrown patches of trees. Only an hour into the trip it felt like we were having our very own “On any Sunday” moment. The British Triplets, singing in harmony and churning up every rock in sight. We were having so much fun we didn’t even have time to think about the rapidly setting sun.

I’d been out in Baja at night before, but that was on a modern bike with headlights that could be seen from miles away. On the Triumphs, putting out enough voltage for some shitty Lucas halogens is a struggle enough – forget expecting them to actually light up the road ahead. So, as we cruised toward the shining beacon of the coast, I reached down and flicked on my light. I sat back and let the dim little flashlight lead the way until I hit the first real bump in the road, and it rattled loose. I’d be operating the light by hand from here on out, like a spotlight in a storm. Nothing better than riding one-handed in the dark, right? With Minchinton and Harper beginning to pull away, I aimed my headlight and took off after them as we crested the highest point of the valley and caught our first glimpse of the ocean. With the moonlight dancing across the midnight blue of the Pacific, we pointed our front wheels downhill and jockeyed for position toward her.

I sat for a moment and smelled the sea. It felt necessary to stop and take it all in. For surfers and riders alike, the sheer access to untainted coastline like this was nothing short of a miracle. But my romantic moment of reflection would be short-lived as I watched the dueling headlights of Minchinton and Harper blow past me and traverse the steep, boulder-ridden downhill to the coast. Dodging hidden rocks, ruts and the occasional lost cattle, every obstacle feels consequential on these old bikes. Maybe that’s what makes them so thrilling to ride. Just making it to your destination feels like you’ve earned something. In our case it would be a hot dinner and a few stiff drinks to wash away the dust.

Following the scent of fresh-brewed coffee, and thinking I was ahead of the game, I walked outside the following morning and found the boys already getting after it. Minchinton, having fallen asleep upright on a couch, was up and ready to jump on the bikes. Harper was checking his beloved machine for any issues, and I figured I’d at least lube my chain and see from what new places oil was escaping. The day’s agenda: Hit the coast and head south. So, we fired up the old gals and rolled out – for a few feet – until we discovered Harper’s sudden gearbox issue. She wouldn’t roll. Not wanting to burn an entire day trying to fix it, we pushed him to the top of the nearest hill we could find. Clicking through gears, trying to bump it, Harper got all the way up into fourth before she would light up. Not wanting to risk another stall, he took off ahead.

Minchinton took the lead, and we chased him into the dirt. Alongside the ocean, we dove in and out of sandy singletracks, throwing the bikes around with ease. We wheelied between each other, jumped any whoop or dirt pile in sight, and battled our way out of town and toward miles of virgin beach. At speed, Harper’s bike was back in the mix, and Minchinton’s 500cc single was humming along and keeping pace with the 650s. Our second day on the bikes was looking like it would eclipse the first. We were fresh, and the machines were holding their own. Then I rounded the next corner and cracked the throttle back, and my bike sputtered to a dead stop. I watched helplessly as Harper and Minchinton drifted away from me.

I pulled my tool roll from my bike and dropped it into the dirt to take a better look. The good news? I had a few fresh spark plugs to test, minus one spark plug wrench. The boys whipped back around to come lend a hand, not having much help in the tool department. With a pair of pliers that barely fit, we backed the plug out and surveyed the issue. What do you know: no spark. Checking a few other could-be culprits, my poor bike appeared to be dead in the water. We gave it one last go and attempted another bump-start. As we kicked it into second, she sputtered and clanked, and just when all hope was lost, my engine roared back to life. I couldn’t believe it. Not wanting to waste a second chance, I turned around and raced past the fellas and aimed for the nearest highway. If shit hit the fan again, at least I could bum a ride into the nearest town, instead of being stranded on some desolate cow trail.

With all the bikes needing some love, we dragged them into a familiar garage of a friendly American expat and did our best mechanic impersonations. Minchinton and Harper got to work on some clutch adjustments while I tore my bike apart, trying to figure out why she insisted on stranding me again. Time was measured in crushed beer cans and shit talk until the sun started setting, and we slapped the bikes back together for a little test run. Harper took off, Minchinton got his bike running, and I prayed to whatever gods that this damn bike would run. She rose from the dead, and I wasted no time in punishing the fragile machine. We banged bars across sections of an old racecourse, lumbering through silt beds and blowing out sandy corners. For all the headaches they occasionally caused, these bikes were unbelievably fun to ride.

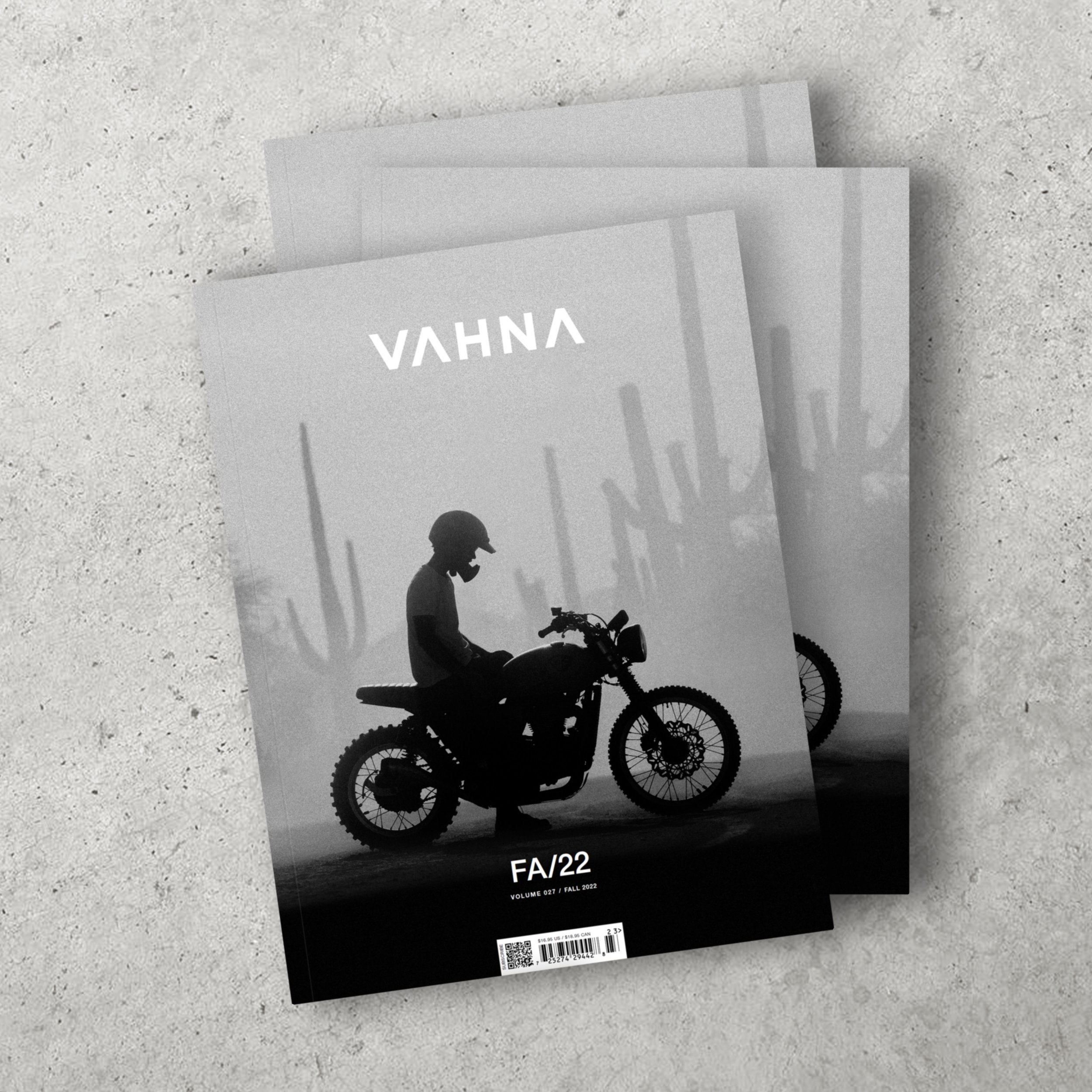

The next day was one of those rides you had to have been on to believe. From the sea, the center of the Baja peninsula rises 10,000 feet to the top of breathtaking peaks. Dusty and dried-out cactus give way to staggering pine forests and views like no other. With the bikes breathing clean air for the first time on the trip, the boys flowed effortlessly through the curves, without a car in sight.

On the edge of the highway, we stumbled upon a perfectly graded dirt track, used by the locals for the occasional “run what you brung” style of auto racing. Were we really going to get to pitch bikes sideways, Mert Lawwill-style, in the middle of nowhere? Mexico fucking rules.

Harper and Minchinton rolled down onto the track to take a better look, and I walked down to the starting line to stage a race between them. Regardless of where you put him, Minchinton is always going to find some way to compete on a motorcycle. Harper was ready to take his shot at the champ. I stood between the two oil-soaked machines. The engines revved wildly, and their eyes focused up ahead. Fingers trembled slightly on clutch levers, ready for the drop of the flag. I reached up and pulled off my cowboy hat, lowering it slowly toward the ground. I bent at the knees, and in one fluid motion hurled my hat into the sky. The dust cloud engulfed me as they took off toward the first corner. Lap after lap, I watched my buddies pitch their Triumphs sideways, battling for the lead. The corners appeared a bit rougher than they looked, as the rear ends danced and stood the boys up from time to time, but there was no stopping them. The sun dropped into the sea yet again and backlit the golden plumes of dust that drifted away from each corner that they slid through. Oh, the places you can go with a motorcycle and a few friends…

On the final day of our ride, my cowboy boots dangled from the truck bed of a lime green Suzuki Samurai, and I was really beginning to ponder my recent life choices. Armed with a Super 8mm camera in one hand and bracing for dear life with the other, I shot some frames of Minchinton and Harper as they ripped up the coast one final time. Heading northbound to document the last remnants of our trip, Minchinton turned on the charm with his suave Spanish and made friends with a local mechanic, recruiting him for the lucrative role of a hired camera car driver. For a few beers and some cash, the fella blew off Mother’s Day with the family and threw a few gringos he just met into his beloved chariot. At speed, the little Suzuki was a far more terrifying ride than that of the Triumphs, especially as we bounced over rocks and ruts a mere few feet from the coastal cliffs.

Eating dust behind us, Minchinton and Harper labored the tired machines toward home. Taking a break to avoid the nausea of Mr. Toad’s wild ride, I watched from above as the boys drew giant figure eights on a desolate beach below. Their tires dug deep ruts into the sand as they shot roost across the beach at each other. A few feet away, as the waves crashed onto land, the high tide slowly took back the temporary scars left by churning wheels. Seagulls dove into the sea, the Suzuki Samurai drifted gracefully across the sand, and atop the sea cliff, I took in the show with pure awe. It didn’t seem possible to do all the things we had done on this trip on these bikes. The local coffee shop runs and weekend rides with the girlfriend back home would never be the same. After Mexico, riding the Triumphs anywhere else besides the beaches, the mountains, or on private dirt tracks would be mundane.

Fifty-something years after the first Triumphs made their mark down here south of the border, our British machines grabbed the torch and ran with it. This trip wasn’t a record-breaking tip-to-tip run or a Baja 1000 race for glory, but it was a watershed moment for all of us. These motorcycles were more than collectors’ items, doomed to sit under dusty covers in a garage. They were meant to be ridden and ridden hard. That’s why we came to Mexico. To test ourselves and our bikes, proving to those who said they wouldn’t survive that these relics could hold their own against a formidable opponent. I gained a deeper respect and admiration for the engineering of decades’ past. Vintage bikes bring a new perspective. They forced you to slow down a bit and see Baja with a fresh new set of eyes.

It felt like déjà vu looking at my bike in the garage, once again in pieces. It had been through hell and back in recent weeks. From racing across the California desert to slogging through countless miles of dirt, sand, and rocks. Minchinton put his 500cc single back in the garage, gave her a nice coat of WD-40, and set her aside. He’d grab another bike, pick a new destination, and begin his next two-wheeled adventure all over again. Harper wasted no time polishing his beauty back to her pre-Mexico glory, eager to resume his regular schedule of canyon rides and wreaking havoc across Malibu. With a growing parts list, I figured I’d take my time and give my bike the attention and respect she deserved. She’d earned it. A month prior, I could’ve been convinced to hang up the open face and sell the vintage bike. But after Mexico, I couldn’t wait to ride her again. I think I’ll crack open an ice-cold cerveza and get to work. The old gal and I have plenty more miles to go.